Lincoln’s only emergency night shelter is busier than ever, but residents have objected to plans to almost double the centre’s capacity. This begs the questions, in a period of nationwide hardship, why can’t we relate to the homeless, and where is our compassion?

Lincoln is renowned for its heritage rather than its issues with homelessness. But it is difficult to walk along the High Street without being asked for spare change by someone camped in a shop doorway or quiet alcove in the Bailgate.

Scores of people walk past these troubled souls on a daily basis, barely noticing them, but when floods devastated Cumbria in recent weeks, raising questions whether hundreds of people would be left without access to their homes over Christmas, the entire nation’s attention was drawn to the issue.

Unlike the flood victims, the majority of the homeless have no one to turn to. The Nomad Trust emergency night shelter offers beds, food, and comfort. This year has been the charity’s busiest, getting a third more “service users” through its doors.

With the service stretched, planning permission was requested for a new shelter able to house 23 homeless people, with a medical consulting room, Internet area and café. Other rooms would consist of a classroom and meeting area, but an 80 signature-strong petition opposing the plans was handed to Lincoln City Council earlier this year.

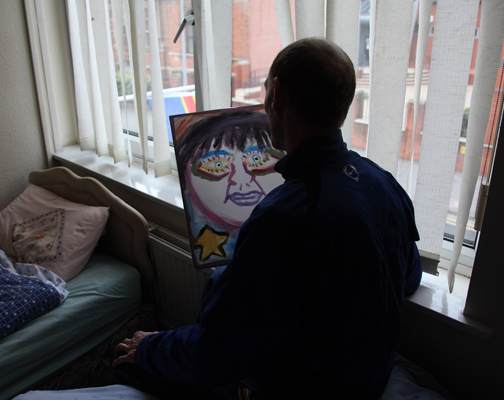

These destitute people are often looked upon as alien and gain little sympathy, but The Linc visited the county’s only emergency night shelter to uncover the story behind Lincoln’s homeless.

The Nomad Trust Shelter, despite being close to the city centre, is by no means on the tourist trail. With a reinforced door and greeting by a stern, inquisitive voice over the intercom this does not seem like a safe heaven.

Upon entering the building you are thrust into a sombre environment, with some disturbed individuals. On the surface there is a group of reasonably young people seated, all taking part in the day’s class, nothing too different from university seminars. In this room there are two paranoid schizophrenics, and a 20-year-old man recently released from prison, after serving a sentence for the manslaughter of his own father.

Gary Widdowson, “Senior Homeless Services Coordinator”, has worked at the centre for nine years and explains that first impressions are not important. “This young lad has served his time for lashing out against an abusive father. He hit him once, knocking him to the ground, and killing him, and for that he has suffered for six years. Now he is just a shy kid like any other,” he says.

It is not well known that one bed for a male and one for a female is reserved by the local prisons for inmates who are newly released but need time to make arrangements for themselves. Widdowson also revealed another worrying aspect of the shelter’s clientele, admitting that many of them turn up with drugs.

“I see everyone who comes through the door and have to make a judgement on whether or not they are dangerous. Even though some of them have problems with addiction or criminal history, I am happy to share my living space with them,” he said.

Widdowson was keen to point out that there is an unjust stereotype surrounding the homeless. People of all ages and social backgrounds can fall into hardship and one of the most common causes of homelessness, in his experience, is the result of relationship breakdowns.

“Surprisingly, young men are amongst the most vulnerable as in a break up it is normally the man that is forced to leave his home. Some people are lucky enough to have the support of family, but a lot of people find themselves homeless temporarily, whether they sleep in their car or resort to the shelter,” Widdowson says.

However, the problem is not with the people who have fleeting encounters with the Nomad Trust, but the ones who find themselves trapped in a “vicious circle” of crime, drugs, and re-offending. A Probation Service officer, who wishes to remain anonymous, explained how many of the service users have been in prison as a result of their drug problems, but clean themselves up and return to society with optimism, only to be pulled back into their previous lifestyle.

“They are surrounded by drug use and other drug users at the shelter and if they do not move on quickly then they end up being drawn back into this world. It makes no sense,” explained the officer.

Moving some of the characters on from the shelter quickly is often a major problem for Widdowson. He says: “The young lad with manslaughter hanging over him isn’t wanted anywhere, but the sad thing is the longer he stays here the smaller his chances of escaping and leading a normal life.”

Heather Lindley, a social worker with 16 years of experience, and former Lincolnshire Social Services county manager, deals with planning how services spend their money. She agrees it is hard to break the mould, and things such as mentoring schemes and connection with Job Centre Plus can help, but these pose problems such as relying on volunteers and not being able to apply for work without having an address.

In Lindley’s experience, the issue is the amount of funding they get and how it is used. “It can be said we live in a ‘nanny state’ giving out handouts, not providing choice or a way out, and many of the service users have mental health or addiction issues and need more than this,” Lindley says.

The Probation Service officer agrees with this, blaming under funding for a tragic end to one of the cases she dealt with.

“Instead of being offered support, an ex-service user was given his disability allowance of around £800 per month in a lump cheque. Being an addict, this provoked a massive binge, with terrible consequences,” she says.

The evidence shows that a bed for the night is not the answer for many of the regulars at the Nomad Trust, but the stigma that continues to surround the homeless has provoked angry residents to block an opportunity for progress.

Anne Stray, an NHS practice manager, identified a problem with getting the support to the homeless, who are notoriously hard to track down. She says: “Sometimes you have to offer services in unconventional places to reach everyone.”

Unfortunately the Nomad Trust may miss out on their opportunity to achieve this. Becca Cliff, a geography and education student at the University of Lincoln, lives on Monks Road near the shelter and was “unaware that it even existed”.

The shelter is open all year, and relies on various forms of donations, amounting to over £100,000 a year. This is achieved through the Trust’s charity shop, numerous donations of tinned goods given during the harvest festival, and local businesses, such as a butcher who gives £1,500 worth of meat every year.

Widdowson praised the local community for their generosity. “One elderly lady calls in on the way back from the shops, and gives us tea bags, along with knitted blankets.”

The shelter clearly deserves public support, but sadly the residents can’t overcome their prejudices.