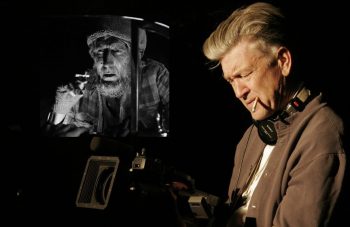

When the question came to my mind as to how I would write an obituary for David Lynch, I found myself struggling with what such a piece of writing would look like. There have already been quite a few obituaries done in the week since the passing of one of cinema’s most complex characters. So, that meant that there wouldn’t be anything in this obituary that hasn’t been mentioned before.

Instead, what I’ve aimed to do is write about what David Lynch’s work has meant to me, his impact on the film industry, and the deeper themes and messages that sum up the work of a true auteur.

My first experience with ‘Lynchian cinema’ was the cult-classic Twin Peaks. I was searching for a new show to watch, and whilst searching I found one called Twin Peaks, a murder mystery from the 90s spanning two seasons, this was before the third season was released in the 2010s. So, I decided to give it a go, what I saw was what I understood to be very emblematic of everything that seemed to make up small-town America during the 90s. Families sat around the table saying grace before they began t9heir evening meal, rebellious, leather-jacket-wearing teens, and communal diners where the inhabitants of a small town would congregate to share their lives with one another.

As I watched the show, I was eagerly awaiting to find out the identity of the killer of Laura Palmer, why was she murdered, and if there were any members of the town of Twin Peaks who had a secret hand in it. As the show went on, I noticed that towards the end things started to get very…surreal. To say the least.

What started as a murder mystery set in a small suburban American town turned into what looked like a study of the deeper workings of the nuclear American suburban family- and by extension the multiple families that make up a small town in the US- with a strangely unexpected and surreal emphasis on the more spiritual aspects of life.

By the end of the series, a villain suspected of killing a teenage girl became a metaphor for the evil that is allowed to permeate through a society that will enable it to take root, and the mundanity of friends sitting with each other enjoying coffee and cherry pie- which may have seemed boring at first sight- became a display of what the show’s creator thought was being eroded as a result of the influence fear/violence perpetuated through the media.

Suddenly, a cancelled TV show from the 90s became reflective of the state of the world during its time and the state it would head towards if it carried on in that same fashion. A film or a TV show about something that would seem small-scale but is a reflection of what happens on a large scale. Welcome to the works of David Lynch.

After being deeply mystified by Twin Peaks I decided to watch some of Lynch’s work over the years which included titles like: Eraserhead, Blue Velvet, Wild at Heart, Twin Peaks Fire Walk with Me, The Straight Story, and Mulholland Drive. For anyone who has seen these films, it may have been too easy to have brushed Lynch off as an eccentric who enjoyed confusing people, but on closer inspection, it seemed as though Lynch was a man who had a profound understanding of the deeper elements of human experiences. Lynch never produced large-scale epics like those put forth by the likes of Lucas, Coppola, or Spielberg, but his work was so dense with meaning he didn’t need a large budget or special effects to impact his audience. He could create a compelling, layered story about the most mundane experiences, and say more about that than most people would be able to.

Nowhere is this more evident than in his film Blue Velvet. Released in 1986, this psychological thriller showed the life of a young suburban man Jeffrey Beaumont (played by Kyle McLachlan, who would later play the protagonist in Twin Peaks) as he is plunged into a world where he is a stranger after finding a human ear in the woods during a walk. After trying to find out more about the ear and who it belonged to, he is trapped in a confusing relationship with a lounge singer (played by Isabella Rossellini) who herself is being held captive by an oppressive local criminal- with a Freudian fixation on his mother-named Frank Booth (Played by Dennis Hopper) who threatens the singer with harm to her child if she does not comply with his demands.

Jeffrey is soon awakened to the cold hard truth that the suburban, picturesque town he grew up in, with its white picket fences, freshly cut lawns, and innocent relationships, is also a place of vice, domestic abuse, and criminal violence.

And this, this is what made Lynchian cinema so enthralling. Lynch’s work- for me at least- seemed to communicate the idea that sometimes the inner workings and unseen elements that are inherent in the everyday monotony of our daily lives are packed with far more fascinating stories that have deeper meanings.

Sometimes the truest form of evil isn’t found in megalomaniacal politicians debating on what buttons to push, sometimes true evil can be found in a small middle-class cul-de-sac.

Sometimes true joy isn’t found in earth-shattering accomplishments, but in being able to spend moments exchanging sweet nothings with our loved ones. The beauty in the mundane is something I would say is a key trait of Lynchian cinema.

This can be seen in his 1999 release ‘The Straight Story’, a film about a World War 2 veteran who hears of his estranged brother’s stroke and decides to go all the way across America to visit him before he dies. The only problem is that he is unable to get a driver’s license due to hearing and vision impairment. So, in a desperate attempt to make amends with his brother, he travels across the States using nothing but his lawn tractor.

What ensues is a story about a very soulful journey that sees its protagonist engage with young and old characters alike, get a taste of what the young people of the country he fought for are becoming, expel old wartime traumas with fellow veterans, and fight to keep what little he has after time has slowly taken his world away from him.

The Straight Story you might say is the one film that doesn’t have the typical Lynch aesthetic. There are no whimsical dream sequences, little people dancing to smooth jazz, no women covered in dirt as an ominous sign of danger, and no criminals carrying oxygen tanks filled with chemicals to cause sexual arousal should they need it. All things that have appeared in Lynch’s films by the way.

And yet, The Straight Story could be seen as the most Lynchian of all of David Lynch’s work. The reason is that there is a sincerity and a heart to the film that most directors can’t capture. And that goes for Lynch’s work as a whole. Anyone who watched and studied his work could see that it was produced by a man who seemed to have an all-encompassing concern for humanity, especially the art and entertainment it consumed.

Being a man of meditation, Lynch was aware of what crass and vulgar expressions of art could do to a person’s being, and his work reflected that of a man trying to restore a sense of balance in a world that was becoming more and more unbalanced as was evident- and still is- with the demand for more graphic depictions of violence and the real-world violence that is broadcast for the whole world to see. Lynch appeared to me as a man trying to use his art to combat the darkness that hang over people’s heads like clouds. His work- to me- seems to call people to not be hollow consumers of violence and all the things that obscure the beauty of life.

His work seemed to celebrate the beauty of the mundane, the idea that cherry pie and coffee with friends can be more fruitful than any thrill-seeking high that we can get, or the fact that an old veteran driving across the US on a tractor can be just as emotionally compelling than a large-scale action adventure, and that often the most normal things tend to be the strangest.

Lynch has left behind a legacy that has seen cinema giants like Scorsese branding him a genius, actors who he worked with like Naomi Watts shaken by his passing, and an entire industry feeling the impact of the loss of one of its giants.

It is the mark of most great men that they, in all things they undertake, express a concern for others, and use their talents and skills to serve others. And I feel like that concern was inherent in all of Lynch’s film, a concern who people, and an attempt at showing them through film what a roller coaster ride the everyday human experience can be, how we lose a being in mindless entertainment, and what can be done to reclaim our humanity.

Lynch was seen as a weird man by a lot of people, and I will not take up any more time trying to defend his eccentricity. But I will leave you with a quote I heard from the American Comedian George Carlin that I feel encapsulates the dynamic between David Lynch and the people who could never understand him.

“Those who dance are considered insane by those who can’t hear the music.”