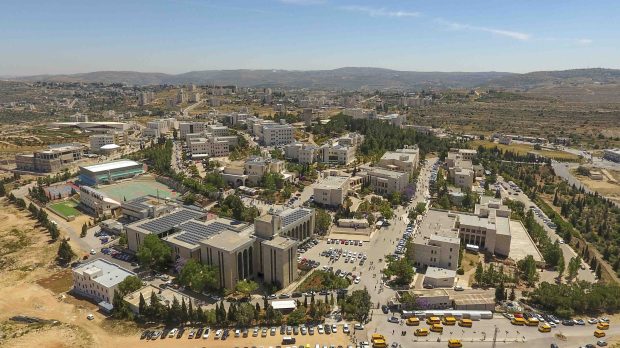

Students and Lecturers gathered on November 28th in the Cargill Lecture Theatre to listen to an informative talk by Dr Aboud Humayel. A specialist and lecturer on Arabic language, literature, philosophy, and cultural studies from Birzeit University, located in the West Bank.

Dr Humayel’s talk was about the subtle/overt implications of the destruction of the University as a physical place where students go to learn and as an institution dedicated to instilling knowledge in its students.

It was put forward to the attendees of this talk that Palestinian students are without classes because the universities are no longer standing, leaving the students with no place to go to pursue their studies.

Dr Humayel’s talk also hinted at the fact that while there is the physical explosion of the university, there is- alongside it- the slow implosion from within the university structure itself in Palestine.

This implosion- Humayel added- was not an overnight phenomenon, rather a slow decline of the university’s initial dedication to truth and justice that has been going on for thirty years.

Dr Humayel pointed out in his talk a paradox that exists for the Palestinian people, but, for the sake of this article, it will be looked at microcosmically through the lense of the Palestinian students.

And that paradox that Dr Humayel pointed out was that there exists the current order that the Palestinian people are under in this case the structure of the university- and within the structure exists the Palestinian people’s goals and dreams, but if they desire freedom the current order must go.

And yet, the anxiety of freedom on the part of the Palestinian people Humayel said was something that keeps freedom- to him at least- more so an idea than an imminent reality.

But this, to the Palestinian lecturer, brought about another paradox, where he stated that: ‘In killing something you remind people why it’s important’.

While the resolution to this issue is still being worked out, another problem relating to things like the conflict in Palestine exists alongside it- and our perception of it- here in the west. And that is the way educational institutions choose to inform their students of how to interpret the events happening in different parts of the world.

Dr Owen Clayton, 43, an English literature lecturer for the University of Lincoln, and Chair of the University College Union, along with fellow colleagues was responsible for putting this talk together. Dr Humayel’s talk was but one aspect of this gathering, the other part was about this matter of ‘decolonizing the curriculum’.

Clayton voiced his concerns- by means of an informal interview- about the lack of diversity in educational curriculums that would include different viewpoints and ways of looking at things that are not just informed by a colonial mindset.

Clayton likened the effort of decolonizing the curriculum to previous movements from different parts of the world i.e. the Rhodes Must Fall, and Black Lives Matter movements from South Africa and the US, where he also mentioned a current effort in the West to re-think the universities relationship to things such as colonialism.

Clayton stated that decolonizing the curriculum meant: ‘including a variety of perspectives that haven’t previously been included’, adding that when this is done it can add an additional layer of context to the previous perspectives that have been taught by the universities before.

Something that the English Literature lecturer wanted to make clear was the need to separate the act of decolonizing the curriculum from cancel culture.

On this Clayton was very clear in differentiating the two, saying that decolonizing the curriculum was about: ‘including more perspectives, and it also means providing additional context’.

Dr Clayton has made mention of the fact that he would keep pushing for effective change to the university curriculum so that a wider depth of understanding on things as pertinent as the conflict in Palestine can be made available to current and future students.

The struggle of the university as a physical entity and as an institution in Palestine, and the push to get Western universities to re-think their methods on how they educate their students about world events past, present, and future, highlight many things.

They represent the desire for a shift in how the university is perpetuated as an institution, and a motivation to include newer perspectives that add another layer of context to world history, and current events so that the university can rejuvenate its reputation as being a place dedicated to knowledge and freedom.