This article was originally published in the Freshers 2015 print edition of The Linc. If you’re a student and want to get your work in print, send us an email and get involved!

Maintenance grants for students from poorer backgrounds will be scrapped next year, following Chancellor George Osborne’s 2015 budget.

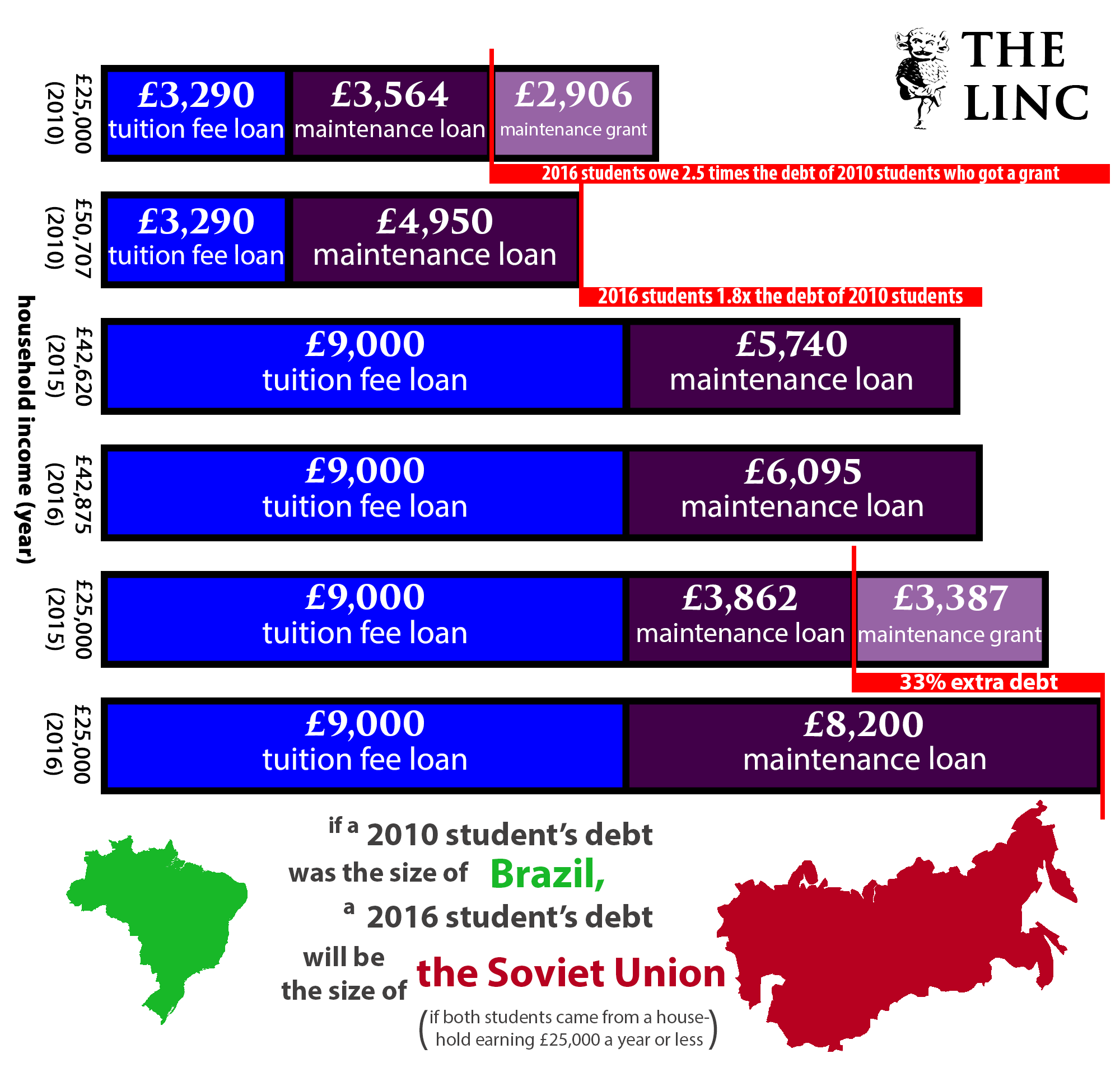

The grants, which are worth up to £3,387 for students from households earning under £25,000 a year, are not repayable; leading Mr Osborne to claim they represent a “basic unfairness in asking taxpayers to fund grants for people who are likely to earn a lot more than them”.

They will be replaced with a larger maintenance loan package of up to £8,200 a year, all of which must be repaid after graduation when graduates are earning £21,000 a year or more.

Students from families earning above the grant threshold (just over £42,500) will also have increased loans: from £5,740 to £6,095 annually.

The changes will only apply to those who begin their courses in 2016 or later.

The Chancellor’s budget announcements also included the potential for tuition fees to start rising with inflation from 2017 – as long as the universities offer “high-quality teaching”.

University Alliance, a group of universities that includes the University of Lincoln, welcomed the move. “Linking tuition fees to inflation is essential if our universities are to offer world class teaching,” said Maddalaine Ansell, the group’s CEO.

“It is reasonable to link the increase to teaching excellence and University Alliance looks forward to working with the government to work out how this can best be done,” she continued.

The University of Lincoln declined to respond to our questions on the potential fee raise “as they’re questions on national [higher education] policy”.

However, a University spokesperson did say that hardship and bursary funding was secure for 2016: “The University of Lincoln will continue to offer students from low income households financial support through bursary funding in 2016/17. All full-time European undergraduates from households with an income of up to £40,000 will be awarded a cash bursary of £500 per level, subject to maintaining satisfactory levels of attendance and engagement.

“The University’s total investment in bursary support varies depending on backgrounds and numbers of new students enrolling, but we anticipate more than half of new students in 2016 will qualify for bursary support.

“The University will also maintain the same total level of hardship funding of almost £300,000 to help individual students facing financial difficulties.”

On the other hand, Rob Ellis, Chair of the National Association of Student Money Advisers (NASMA), said whilst he was “pleased to see the potential of more money being provided directly to students to help meet their cost of living, we are extremely concerned at the impact this will have on access rates for disadvantaged students.

“The ethos of this policy seems to be ‘the lower your income, the more debt you can have’, which contradicts the widening participation strategy many have worked so hard to implement within Higher Education,” he added.

But what do prospective applicants think of the changes? The Linc spoke to some future students at one of the University’s summer open days, less than a week after the budget was revealed.

Tom (17) from Hertfordshire told us: “It has made me think twice about going to any university. We come from a working class background, so we can’t fund our way through uni by ourselves. It’ll leave me with twice as much debt as I thought I’d have originally. I knew it was expensive in the first place, so I was preparing, but it’s way too extortionate now.”

Tom (17) from Hertfordshire told us: “It has made me think twice about going to any university. We come from a working class background, so we can’t fund our way through uni by ourselves. It’ll leave me with twice as much debt as I thought I’d have originally. I knew it was expensive in the first place, so I was preparing, but it’s way too extortionate now.”

Two Huddersfield friends, both 17-year-olds named Rebecca, had differing opinions. One said: “It has put me off a bit. My dad was talking about how it would be a tight squeeze to afford things like accommodation.” The other Rebecca disagreed, saying: “It hasn’t put me off because I don’t think you can get a good job these days without going to uni, so you kind of have to go to have a good life.”

Two Huddersfield friends, both 17-year-olds named Rebecca, had differing opinions. One said: “It has put me off a bit. My dad was talking about how it would be a tight squeeze to afford things like accommodation.” The other Rebecca disagreed, saying: “It hasn’t put me off because I don’t think you can get a good job these days without going to uni, so you kind of have to go to have a good life.”

Finn, a 17-year-old from Nottingham, noted that “it’s not entirely clear what you’re going to do afterwards and how you’re going to pay it back. In the end, everyone wants to go to university just for the experience of having a higher education, which makes you more likely to get a job. But I know some of my friends have decided not to go now because of the increase in fees.”

Finn, a 17-year-old from Nottingham, noted that “it’s not entirely clear what you’re going to do afterwards and how you’re going to pay it back. In the end, everyone wants to go to university just for the experience of having a higher education, which makes you more likely to get a job. But I know some of my friends have decided not to go now because of the increase in fees.”